They say that Lake Superior is the lake that never gives up her dead, and demands respect from all those who dare to come near. Most of the things I share regarding the lake are fun ways to get out and enjoy all that she has to offer, but this post shares something different. On the stormy night of November 10th, 1975, exactly 50 years ago, the SS Edmund Fitzgerald lost all communication with other ships and disappeared off the radar forever. As Canadian legend Gordon Lightfoot says in his iconic song, the gales of November came early, marking the last voyage of the ship. If you’ve never heard of this tragic event that lost a crew of 29 men, I encourage you to keep reading. And if you’re already familiar with the wreck, read on and let me know other interesting facts from that night that I missed. Also, see if you can spot all my Easter eggs from the song 😉

Quick pause, October was a super hectic month, and I high-key disappeared, but I’m making my slow return. This semester is over in about a month, which means I’m in crunch time, but I had to churn out a post for the 50th anniversary of the Fitz’s sinking.

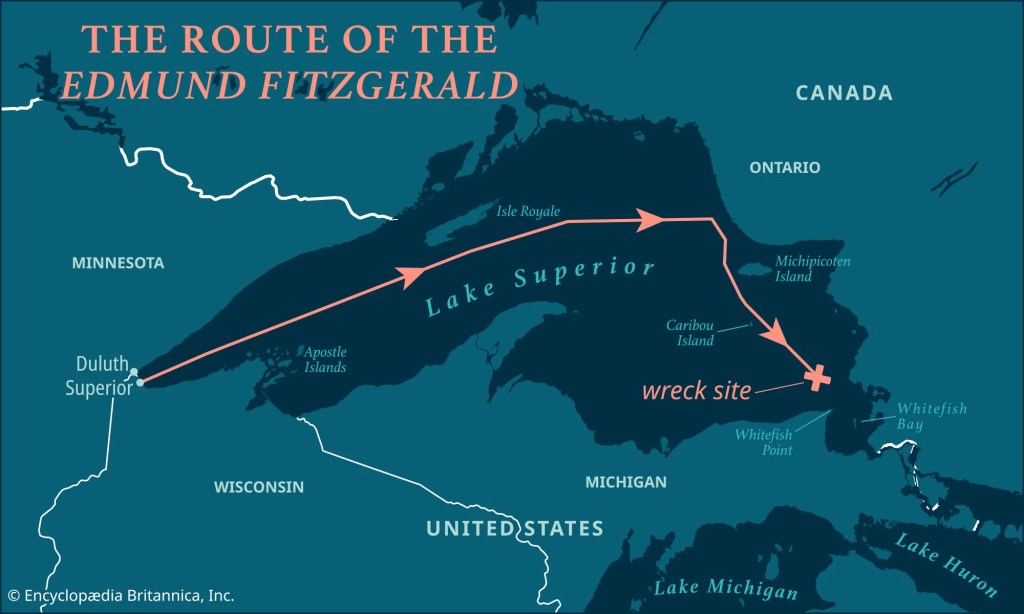

The ship was first launched in June of 1958 and saw its maiden voyage in September of that year. On November 9th, 1975, the ship set out from Superior, Wisconsin, on the west side of the lake, heading for Zug Island in Detroit, crossing through the Great Lakes system. The ship was carrying iron ore, specifically 26,000 tons more than the Edmund Fitzgerald weighed empty. The ship was the largest on the Great Lakes and had made trips from Superior to the lower lakes several times before.

The ship set out on what we know as its final voyage on November 9th at around 2:30 pm, carrying a crew of 29 men, most hailing from Ohio and Wisconsin, among other states. That day, the National Weather Service issued a gale warning for the areas that the ship would be sailing through. The ship met up with the S.S. Arthur M. Anderson on the water, which was 15 miles behind it, and kept in close radio contact with it as it headed into the storm.

As the weather picked up, the Edmund Fitzgerald and the Arthur M. Anderson were in close communication. The Fitzgerald reported taking on heavy water and the loss of its radar systems. The ship asked the Anderson to help it continue navigating, and the other ship kept an eye on it. Closer to 5pm on the 10th, the Fitzgerald sent out a radio signal asking any ship in the area to help locate the whereabouts of the Whitefish Point beacon. The Avafors responded, letting the Fitzgerald know that the beacon was not operating due to a power outage.

The waves were so rough that the old cook came on deck, sayin’, “Fellas, it’s too rough to feed ya.” At 7pm, a main hatchway caved in, he said, “Fellas, it’s been good to know ya.” At around 7:10 pm, the final radio conversation between the Anderson and the Fitzgerald happened. The Anderson called to report another ship approximately 9 miles ahead, and so to keep watch. The Anderson also inquired about how the ship was doing without its radar and the heavy waters it was taking on. Captain McSorely responded by saying, “We are holding our own,” and that was the last message sent from the ship before its fatal overtaking by the lake.

The Fitzgerald disappeared from the Anderson’s radar, prompting a call to the Coast Guard. The Anderson also reported not having a visual on the ship when it should have been in range to see its lights. The Anderson took the lead in the search for the ship, only finding two lifeboats and some other debris during the storm. None of the 29 crew members were found. In May of 1976, the wreck was officially found, identified by the words “Edmund Fitzgerald” on the upside-down stern. In 1995, the bell of the ship was raised from the lake, and replaced with a new bell that contained the names of the 29 men who were lost. The original bell is on display at the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, near Paradise, Michigan.

Lake Superior is a magical place, in my opinion. It’s a must-visit place for anyone, and should be on your bucket list if it isn’t already. The lake attracts millions of people each year, of all ages. She is a slice of paradise for many, but is a force to be reckoned with and is said not to give up her dead. Hundreds of ships sit at the bottom of the lake, and each year on November 10th, extra recognition is paid to those who have lost their lives and loved ones. To quote Lightfoot one more time,

“The legend lives on from the Chippewa on down

Of the big lake, they call Gitche Gumee

Superior, they said, never gives up her dead

When the gales of November came early.”

All of the information that I used to write this came from the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum website and SS Edmund Fitzgerald Online. I encourage you to check out these sites for more info! I am also including a list of each of the crew members, with their hometown and job as a part of the crew, as some sort of tribute to the event.

- Michael Armagost, Iron River, Wisconsin, Third Mate

- Frederick Beetcher, Superior, Wisconsin, Porter

- Thomas Bentsen, St Joseph, Michigan, Oiler

- Edward Bindon, Fairport Habor, Ohio, First Assistant Engineer

- Thomas Borgeson, Duluth, Minnesota, Maintenance Man

- Oliver Champeau, Sturgeon Bay, Wisconsin, Third Assistant Engineer

- Nolan Church, Silver Bay, Minnesota, Porter

- Ransom Cundy, Superior, Wisconsin, Watchman

- Thomas Edwards, Oregon, Ohio, Second Assistant Engineer

- Russell Haskell, Millbury, Ohio, Second Assistant Engineer

- George Holl, Cabot, Pennsylvania, Chief Engineer

- Bruce Hudson, North Olmsted, Ohio, Deck Hand

- Allen Kalmon, Washburn, Wisconsin, Second Cook

- Gordon MacLellan, Clearwater, Florida, Wiper

- Joseph Mazes, Ashland, Wisconsin, Special Maintenance Man

- John McCarthy, Bay Village, Ohio, First Mate

- Eugene O’Brien, Toledo, Ohio, Wheelsman

- Karl Peckol, Ashtabula, Ohio, Watchman

- John Poviach, Bradenton, Florida, Wheelsman

- James Pratt, Lakewood, Ohio, Second Mate

- Robert Rafferty, Toledo, Ohio, Steward/Cook

- Paul Riippa, Ashtabula, Ohio, Deck Hand

- John Simmons, Ashland, Wisconsin, Wheelsman

- William Spengler, Toledo, Ohio, Watchman

- Mark Thomas, Richmond Heights, Ohio, Deck Hand

- Ralph Walton, Fremont, Ohio, Oiler

- David Weiss, Agoura, California, Cadet

- Blaine Wilhelm, Moquah, Wisconsin, Oiler

- Ernest McSorely, Toledo, Ohio, Captain